Case of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach

|

| Rabbi Moshe Feinstein BANNED Music by Shlomo Carlebach back in 1959 |

Serial Sexual Predator

Sexually Assaulting Women and Teenage Girls Worldwide

Neo-Hassidic rabbi and

singer

Call to Action: Accountability in the

Portrayal of Shlomo Carlebach --

Tzadduk (saint)? Serial Sexual

Predator?

November 3, 2004

Some of you may be aware of the fact that for the last

10 years there has been a movement to glorify the accomplishments of a man

named Shlomo Carlebach. The Awareness Center firmly believes there is a problem

in doing this. There have been numerous accusations that Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach

sexually harassed and assaulted many young women, and sexually assaulted/abused

a few teenage girls.

-

The Awareness Center is looking for survivors of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach who would want to be interviewed by a journalist and have their story published. If you are interested, please contact Vicki Polin for more information.

-

-

The Awareness Center asks that when ever an article comes out regarding Shlomo Carlebach you it to us, including a link on the page it was found.

-

-

The Awareness Center asks that you write letters to editors requesting accountability in the portrayl of Shlomo Carlebach. Please forward your letters to The Awareness Center and send a note giving us permission to publish your letter on our web page.

_________________________________________________________________________________

|

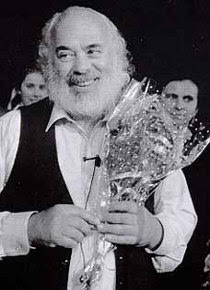

| Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach |

Allegations of sexual misconduct against Rabbi Shlomo

Carlebach can be dated back to the 1960's. Among the many people

Lilith Magazine spoke with, nearly all had heard

stories of Rabbi Carlebach's sexual indiscretions during his more than

four-decade rabbinic career. Spiritual leaders, psychotherapists, and others

report numerous incidents, from playful propositions to actual sexual contact.

Most of the allegations include middle-of-the-night, sexually charged phone

calls and unwanted attention or propositions. Others, which have been slower

to emerge, relate to sexual molestation.

Rabbi Carlebach was seen as "being bigger then life",

"He touched many people on a level that they have rarely been touched in

their lives." Such idealization was only the beginning of a process of canonizing

Rabbi Carlebach, a process that has continued since his death. A number of

his followers told Lilith Magazine that Rabbi Carlebach, when alive, "walked

with the humblest of the humble" and "never said he was a holy man." But

with his death came an outpouring of love, and a degree of idolization that

did not easily allow followers to recognize what others gently call his "shadow

side.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Serial Sexual Predator - Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach

_________________________________________________________________________________

Serial Sexual Predator - Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach

As you watch this film clip that glorifies this sexual predator, it is important remember that Carlebach was kicked out of the orthodox world after numerous allegations of clergy sexual abuse were made. It is also believed that in every town he visited throughout his 40 year career he left a string of female survivors of sexual assault (both adults and children).

__________________________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer: Inclusion in this website does not constitute a recommendation or endorsement. Individuals must decide for themselves if the resources meet their own personal needs.

Table of

Contents:

-

Speaking Lashon Hara about the Dead (01/19/2006)

-

Shlomo Carlebach

-

Testmonials

-

Video Tapes of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach

1994

1998

- Shlomo Carlebach's Obituary (10/22/1994)

1998

-

A Paradoxical Legacy: Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach's Shadow Side (Spring/1998)

-

Sex, the Spirit, Leadership and the Dangers of Abuse (1998)

-

FEATHERMAN FILE (03/201998)

- Rabbi Yaakov Aryeh Milikowsky supporter of Shlomo Carlebach

2003

-

Can New Agers Channel the Old Rebbes' Spirit? - Our Scribe Visits a Neo-Chasidic Confab, Looking for 'Awakening' and 'Renewal' (04/13/2003)

-

When Melodies, Torah Scholars, and Abuse Collide (03/2003)

-

The Carlebach phenomenon (November 13, 2003)

- Letter to the Editor - Jerusalem Post (11/14/2003)

2004

-

Honoring Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach? (07/15/2004)

- Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach Way (07/14/2004)

-

Kashrut.org Discussion on Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach (07/23/2004)

-

Call to Action - Those who live in New York City (09/02/2004)

-

Urgent Call to Action (09/07/2004)

-

First Carlebach conference to grapple with issue of abuse head on; opposition to street naming (09/08/2004)

-

Letters to the Community #7 Board (New York City) regarding street naming (09/010/2004)

-

Victoria Polin, Executive Director - The Awareness Center

- Rabbi David J. Zucker

-

- Location Change (09/013/2004)

- Application Withdrawn - Hearing Canceled (09/014/2004)

- Call to Action: Honoring Carlebach? (10/04/2004)

-

Call to Action: Accountability in the Portrayal

of Shlomo

Carlebach (11/03/2004)

-

Memories Of Shlomo - Conference participants revel in

Carlebach on his 10th

yahrtzeit. (11/03/2004)

- Letter to the Editor - Israel David Fishman

-

Memories Of Shlomo - Conference participants revel in

Carlebach on his 10th

yahrtzeit. (11/03/2004)

- Rabbis Ordained by Shlomo Carlebach

- (Revised) Call to Action: Accountablility in the Portrayal of Shlomo Carlebach (11/12/2004)

-

Carlebach's Legacy Lives

On (11/12/2004)

- Letter to the Editor regarding Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach (Baltimore Jewish Times) (11/12/2004)

2006

- Story About Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach (03/06/2006)

2007

-

Ariela's Story: A Survivor of Shlomo Carlebach Speaks Out (02/26/2007)

Stop the Music? (02/26/2007)

2009

-

Carlebach's Days in Lubavitch (11/08/2009)

2012

- Only in NY: Broadway Musical About Sexual Predator - Shlomo Carlebach

(08/16/2012) - CALL TO ACTION: Stop Musical About Serial Sexual Predator - Shlomo Carlebach (08/20/2012)

Alleged and Convicted Sex Offenders Connected to Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach

-

Case of Rabbi Mordechai Gafni (AKA: Marc Gafni, Mark Gafni, Marc Winiarz, Mordechai Winiarz, Mordechai Winyarz)

-

Case of Rabbi Michael Ozair (AKA: Rabbi Michael Ezra - Kabbalah Coach, Rabbi Michael Ezra Ozair, Rabbi Michael)

-

Case of Rabbi Mordecai Tendler (AKA: Mordy Tendler)

-

Case of Rabbi Hershy Worch (AKA: Rabbi Jeremy Hershy Worch)

Lashon Hara about the Dead

Let Them Talk: The Mitzvah to Speak Lashon

Hara

By Rabbi Mark Dratch

Is it permissible for victims of a perpetrator who

has since died to speak lashon hara about him?

The Talmud indicates that there is no prohibition of

speaking lashon hara about the dead, either because the dead do not know

what is being said about them or because they do not care what is being said

about them.<91> However, because their legacies are at stake, as well

as the reputations and well-being of their surviving families, and because

they cannot defend themselves, Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 606:3 cites a takanat

kadmonim (ancient enactment) that prohibits "speaking ill of the

dead."<92> Hafetz Hayyim rules:

And know also that even to disparage and curse the

dead is also forbidden. The decisors of Jewish law have written that there

is an ancient enactment and herem (ban) against speaking ill of and defaming

the dead. This applies even if the subject is an am ha-aretz (boor), and

even more so if he is a Torah scholar. Certainly, one who disparages [a scholar]

commits a criminal act and should be excommunicated for this, as is ruled

in Yoreh De'ah 243:7. The prohibition of disparaging a Torah scholar applies

even if he is disparaging him personally, and certainly if he is disparaging

his teachings.

However, despite this enactment, there are times when

one is permitted to speak ill of the dead. It is important to note that this

prohibition is not derived from the Torah verse banning lashon hara; it stems

from a rabbinic decree and is, thus, no more stringent than the laws of lashon

hara themselves. Since lashon hara which is otherwise biblically prohibited

is allowed if there is a to'elet, so too lashon hara about the deceased is

permitted if there is a to'elet. While the nature of the to'elet may

change—after all, the deceased is no longer a threat to anyone else's

safety—there may be any number of beneficial purposes in sharing this

information including: preventing others from learning inappropriate behavior,

condemning such behavior, clearing one's own reputation, seeking advice,

support, and help, one's own psychological benefit, and validating the abusive

experience of others who may have felt that they, and no one else, was this

man's victim.

Furthermore, the restriction on speaking ill of the

dead may be based on the assumption that death was a kapparah, i.e., it was

an atonement for sins. This atonement, however, is predicated on his having

repented before his death,<93> and that repentance requires both

restitution for the harm caused and reconciliation with the

victim.<94> If the perpetrator had not reconciled with his victim,

no atonement was achieved. And of such an unrepentant sinner the verse teaches,

"The memory of the just is blessed; but the name of the wicked shall rot"

(Proverbs 10:7).<95>

In addition, Jewish law does not recognize the concept

of statute of limitations in these matters.<96>

<91> Berakhot 19a :

Rabbi Yizhak said: If one makes remarks about the dead,

it is like making remarks about a stone. Some say [the reason is that] they

do not know, others that they know but do not care. Can that be so? Has not

R. Papa said: A certain man made derogatory remarks about Mar Samuel and

a log fell from the roof and broke his skull? A Rabbinical student is different,

because the Holy One, blessed be He, avenges his insult.

<92> See Mordekhai to Bava Kama, nos. 82 and 106.<93> Yoma 85b; See Sha'arei Teshuvah 4:20.<94> See Bava Mezi'a 62b.<95> See Yoma 38b.

<96> See Sanhedrin 31a and Hoshen Mishpat 98:1.

Shlomo Carlebach

Birth: 1926 in Berlin, Germany

Death: October 20, 1994 in New York, New York

Source: Religious Leaders of America, 2nd ed. Gale

Group, 1999.

|

| Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach Partying |

Carlebach's real talent began to manifest itself in

other directions, however, when he emerged as a talented singer and guitarist.

His modernized Hassidic songs, which he performed accompanying himself on

the guitar, struck a responsive cord among contemporary Jewish young people

during the 1960s. He began to develop a unique combination of traditional

Hassidic mysticism and orthodox Jewish practice that seemed to many to resonate

with basic themes in the youthful, "hippie" counter-culture. His form of

Judaism included a place for health foods, communalism, and the search for

self-fulfillment.

Among the most committed of the respondents to his

music and message, in 1969 Carlebach organized the House of Love and Prayer,

a havurot or commune, in San Francisco. (Havurots had emerged among Jewish

youth earlier in the 1960s. Possibly the most famous commune was the Havurot

Shalom in Boston.) During the 1970s as many as 40 people lived with the group.

Through them Carlebach was responsible for initiating two periodicals--Holy

Beggers' Gazette and Tree Journal. A similar community, Or Chadash, emerged

among his followers in Los Angeles.

Since the early 1970s Carlebach has spent a significant

part of the years traveling both across America and to Jewish communities

abroad. He developed a following in Israel and it was there that a third

communal group, Mishav Meot Midin, a communal farm, was formed. Its founding

occurred about the same time the House of Love and Prayer disbanded in San

Francisco, and several former members of the house moved to Israel.

Through the 1980s, the synagogue, the community, and

Israel gave organizational focus to Carlebach's roving ministry. He has adapted

his message to the New Age Movement, and feels a new age is coming as humanity

recognizes the limitations of scientific knowledge. As a new higher heavenly

knowledge spreads among people, Carlebach believes Jews will have a special

role to play, reminding the world that there is only one God. To further

his work, he recorded approximately 25 albums and several songbooks.

Carlebach centered his activity on Israel and the Moshao

or Modin congregation which he had founded in Tel Aviv. He lived in Israel

and New York where he and his brother shared duties for Kehillath

Yaakov.

FURTHER READINGS

American Jewish Biographies. New York: Facts on File,

1982. 493 pp.

Jacobs, Susan. "A New Age Jew Revisits Her Roots."

Yoga Journal (March/April, 1985), 32-34, 59.

"Of God & Blintzes." The New Sun 1, 2 (January

1977), 18-22. Shir, Leo.

"Shlomo Carlebach and the House of Love and Prayer."

Midstream (February 1970), 27-42. Weintraub, Michael, and Michele Weintraub.

"Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach: Half a Story, Half a Prayer." New Directions 27

(1977), 9-15.

SOURCE CITATION

"Shlomo Carlebach." Religious Leaders of America, 2nd

ed. Gale Group, 1999. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington

Hills, Mich.: The Gale Group. 2003.

Testmonials

http://www.carlebachfamily.com/neila.html

"Rebbitzen Neila is the most extraordinary teacher.

Hashem has blessed her with an unusual ability to convey complex and deep

hashkafah (concepts) and kabbalah in a way that makes them understandable

and relevant to the general public."

Rabbi

Mordecai Tendler,

Kehilath New Hempstead, NY

_________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________

Rabbi

Shlomo Carlebach, the foremost songwriter in contemporary Judaism, who

used his music to inspire and unite Jews around the world, died on

Thursday at Western Queens Community Hospital. He was 69 and lived in

Manhattan, Toronto and Moshav Or Modiin, Israel.

The cause of death was a heart attack, according to his sister-in-law, Hadassa Carlebach.

Rabbi

Carlebach put the words of Jewish prayer and ceremony to music that is

heard at virtually every Jewish wedding and bar mitzvah, from Hasidic to

Reform.

In a recording career that stretched over 30 years, the

rabbi sang his songs on more than 25 albums. His most famous song was

"Am Yisroel Chai" ("The People of Israel Live"), which was an anthem of

Jews behind the Iron Curtain before the fall of Communism. It continues

to be sung at Jewish rallies and celebrations today.

One of Rabbi

Carlebach's few English songs, about the beauty of the Jewish Sabbath,

begins, "The whole world is waiting to sing the song of Shabbos."

Rabbi

Carlebach was constantly on tour, rushing from one capital to another.

He appeared in large concert halls, like Carnegie Hall in New York and

the Opera Palace in St. Petersburg, as well as synagogue basements and

college coffeehouses.

In the last year, Rabbi Carlebach gave concerts in Morocco, Australia, France, Germany, Austria and Israel.

Rabbi

Carlebach, who was Orthodox, had a full head of white curls and a white

beard that he pinned back rather than cut, and wore a trademark white

shirt and vest. He operated outside traditional Jewish structures in

style and substance, and spoke about God and His love in a way that

could make other rabbis uncomfortable. "Holy brothers and sisters, I

have something really deep to tell you," was his way of addressing a

crowd.

At the end of Yom Kippur, what most rabbis call the most

solemn day of the year, Rabbi Carlebach would joyously sing and dance

late into the night.

Most of his songs seemed to have no ending,

but would keep going and going until the crowd was exhausted. The rabbi

would rise and tell an elaborate Hasidic tale or bit of Torah wisdom

until he began another song.

Shlomo Carlebach was born in 1925 in

Berlin, where his father, Naftali, was an Orthodox leader. The family,

which fled the Nazis in 1933, lived in Switzerland before coming to New

York in 1939. His father became the rabbi of a small synagogue on West

79th Street, Congregation Kehlilath Jacob; Shlomo Carlebach and his twin

brother, Eli Chaim, took over the synagogue after their father's death

in 1967.

He studied at the Yeshiva Torah Vodaath in Brooklyn and

at the Bais Medrash Gavoah in Lakewood, N.J. From 1951 to 1954, he

worked as a traveling emissary of the Grand Rabbi of Lubavitch, Rabbi

Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

|

| Sexual Predator, Shlomo Carlebach talking with Bob Dylan |

During that period, he also picked up a

guitar and began writing songs and visiting coffeehouses and clubs in

Greenwich Village, where he met Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger and other folk

singers. They encouraged his singing career and helped the rabbi get a

spot at the Berkeley Folk Festival in 1966. After his appearance, he

decided to remain in the Bay Area to reach out to what he called "lost

Jewish souls," runaways and drug addicted youths. He founded a

communelike synagogue called The House of Love and Prayer.

"If I

would have called it Temple Israel, nobody would have come," he said. "I

had the privilege of reaching thousands of kids. Hopefully I put a

little seed in their hearts."

Eleven years later, he closed the

House of Love and Prayer and took the remnants of the congregation to

Israel, where he established the small settlement of Moshav Or Modiin,

in Lod, near Ben Gurion Airport. The settlement now has about 35

families.

Rabbi Carlebach is survived by his wife, Neila

Carlebach, and two daughters, Neshama and Nadara, all of Toronto, and a

sister, Shulamith Levovitz of Monsey, N.Y.

The funeral will be on Sunday at 9 A.M. at Congregation Kehilath Jacob, 305 West 79th Street, in Manhattan.

A Paradoxical Legacy: Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach's Shadow Side

Lilith

Magazine Volume 23, No. 1/Spring 1998

By Sarah Blustain

An orthodox rabbi by training, Rabbi Carlebach took

down the separation between women and men in his own synagogue, encouraged

women to study and to teach Jewish texts, and gave private ordination to

women before most mainstream Jewish institutions would. Described as a musical

genius, Rabbi Carlebach's melodies, including Adir Hu, AmYisroel Chai, and

Esa Ena, are sung throughout the world in Hasidic shteibels and Reform temples

alike; have sunk so deeply into Jewish consciousness that many don't realize

these are not age-old tunes. And Rabbi Carlebach encouraged women, tossing

out loudly a challenge to the orthodox teaching that women's voices should

not be heard publicly lest they arouse men.

Shlomo

Carlebach also abandoned the Orthodox injunction that men and women not touch

publicly. Indeed, he was known for his frequent hugs of men and women alike,

and often said his hope was to hug every Jew, perhaps every person, on

earth.

Shlomo

Carlebach also abandoned the Orthodox injunction that men and women not touch

publicly. Indeed, he was known for his frequent hugs of men and women alike,

and often said his hope was to hug every Jew, perhaps every person, on

earth.

It is an alarming paradox, then, that the man who did

so much on behalf of women may also have done some of them harm. In the three

years since Rabbi Carlebach's death, at age 69, ceremonies honoring his life

and work have been interrupted by women who claim the Rabbi sexually harassed

or abused them. In dozens of recent interviews, Lilith has attempted to untangle

and to explain Rabbi Carlebach's legacy.

"He was the first person to ordain women, to take down

the mechitza

and I think he thought all boundaries were off," says Abigail Grafton, a

psychotherapist whose Jewish Renewal congregation in Berkeley, California

has spent the last six months trying to cope with the allegations.

While Rabbi Carlebach was never formally connected

with the Jewish Renewal movement, which encourages spiritual and mystical

expressions of Judaism, his teachings and music have had a deep impact on

many Renewal congregations, and on institutions of other streams of Judaism

as well. For this reason, he was a frequent guest at synagogues, youth

conventions, Jewish summer camps and other gatherings.

Among the many people

Lilith spoke with, nearly all had heard

stories of Rabbi Carlebach's sexual indiscretions during his more than

four-decade rabbinic career. Spiritual leaders, psychotherapists, and others

report numerous incidents, from playful propositions to actual sexual contact.

Most of the allegations include middle-of-the-night, sexually charged phone

calls and unwanted attention or propositions. Others, which have been slower

to emerge, relate to sexual molestation.

The story appears to date back to the 60's when Rabbi

Carlebach had moved away from his Lubavitch Hasidic practice and was exploring

ways to bring aspects of Judaism to a mixed-gender, secular Jewish community.

But it begins for our purposes in the days after his death, in 1994, when

a memorial service on Manhattan's Upper West Side was attended by a multitude,

and the blocks in front of his synagogue, the Carlebach Shul, had to be closed

off to accommodate the gathered crowds. In pouring rain, men and women wailed

as their religious leaders articulated their grief. "The air around here

is sanctified, "one passionate speaker told the crowd. "If I were you, I

would breathe the air&It will fix something."

|

| Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach at one of his cult like gatherings |

"I hear people say or imply it over and over again,

'He was bigger than life,'" remarks Patricia Cohn, a member of the Berkeley

Jewish Renewal community and a women's rights activist who has been centrally

involved in her community's effort to grapple with the allegations that women

both in Berkeley and elsewhere were injured by Rabbi Carlebach. "He touched

many people on a level that they have rarely been touched in their

lives."

|

| Zalman Schacter-Shalomi with Shlomo Carlebach |

Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb, a pioneer Jewish feminist who

was at that ALEPH Kallah, says that she "first became aware of his glorification

at the gathering, when it was announced that this [memorial] was going to

happen." Right after the announcement, three or four people "jumped me",

she says, and told their stories: "'Shlomo molested me, Shlomo was abusive

to me,'" is how she summarizes their words.

It was going "overboard to not acknowledge the problematic

side of the man when there members of the community there were hurt by him,"

says Rivkah Walton, an ALEPH program director, who reports that she walked

out of the memorial.

In 1997, through the Internet and in public forums,

the stories of inappropriate behavior began to be more widely discussed.

The messenger was Rabbi Gottlieb, who since the ALEPH gathering had been

distressed by the continued murmuring about Rabbi Carlebach. Understanding

the pain and confusion here revelations might stir up, but concerned with

what she saw as the "deification of Shlomo Carlebach"; Rabbi Gottlieb wrote

a tell-all essay.

"These are difficult words to write," she began, in

an essay sent to Lilith and presented by Rabbi Gottlieb at Chochmat HaLev,

a Berkeley Jewish center for meditation and spirituality, in late 1997. "I

have a responsibility to the women who have confided in me. They deserve

a place on the page of the collective memories about Shlomo Carlebach."

She wrote of Rabbi Carlebach's molestation of one of

her congregants, Rachel, as a young woman. As Rachel (name changed on her

request to prevent further trauma) told Lilith in a subsequent telephone

interview, she was in high school in the late '60's when she attended a Jewish

camp where, for the first time in her life she felt 'safe and

uncriticized&Every talent I had was encouraged." Music was everywhere,

and it was to this "safe" environment that Rabbi Carlebach, who spent much

of his life traveling to bring his music and prayer to communities, worldwide,

was invited as a guest singer. "We had heard that someone fabulous was coming,

a star," she recalls of the visit. 'The rabbis [at the camp] really seemed

to honor him, like a god." Rabbi Carlebach, with his warmth and charisma,

was like the Pied Piper, she remembers, and his singing was wonderful; Rachel

recalls it as "the first time in a Jewish context that I could feel that

I was having a spiritual experience."

When he asked her to show him around the camp, Rachel

says she felt, "what an honor [it was] to be alone with this great man."

They walked and talked of philosophy and Israel, of stars and poems, and

she remembers being "just enchanted." He asked her for a hug, and when she

agreed, "he wouldn't let go. I thought the hug was over and I tried to squirm

out of it. He started to rub and rock against me." So unsuspecting was she,

she says, "that at first I thought, 'was this some sort of davening?'" She

says she tried to push him away while he was "dry humping me until he came."

And although she doesn't remember the words he spoke, she remembers him

communicating to her that it was something special in her that had caused

this to happen. "It felt cheap, but he had said thank you." The next day

he didn't even acknowledge her presence.

Rachel's responses, she reports, were varied in the

days after this incident. At first she wondered, "Was I his special friend?"

Then, when he ignored her, she wondered, "Did I displease him? Was he considering

me a whore?" She also blamed herself for causing the event, was there something

special in her that made this happen? And "for not having the chutzpah to

kick him in the shins."

However, he was a special rabbi, and those she had

looked up to, looked up to him. Rachel, today and artist and a martial arts

teacher in New Mexico, told almost no one what had happened. Those she did

tell said he was "just a dirty old man." Thirty-five years later she was

jogging with Rabbi Gottlieb, both her friend and her congregational rabbi,

when they were talking about Rabbi Carlebach. Hearing that others were claiming

experiences similar to hers, Rachel broke down in tears. Only then, she recalls,

did she get very angry. I felt acknowledged. It wasn't a dream, it really

happened."

Other stories have begun to emerge, suggesting that

Rachel's experience was not unique. Robin Goldberg, today a teacher of women's

studies and a research psychoanalyst on women's issues in California, was

12 years old when Shlomo visited her Orthodox Harrisburg, Pennsylvania community

to lead a singing and dancing concert. He invited all the young people for

a pre-concert preparation. And it was during the dancing that he started

touching her. He kept coming back to her, she reports, whispering in her

ear, saying "holy maidele," and fondling her breast. Twelve years old and

Orthodox, she says she didn't know what to think. Her mother, that afternoon,

told her she must have been mistaken, and that she must not have understood

what was going on. But when she was taken to a dance event led by Rabbi Carlebach

years later, while she was in college, she reports that the same thing, dancing,

whispering, fondling, happened to her again.

Another story comes from Rabbi Goldie Milgram, 43,

today a teacher and an associate dean at the Academy for Jewish Religion

in New York City. Rabbi Milgrom was 14 when Rabbi Carlebach was a guest at

her United Synagogue Youth convention in New Jersey, and was invited by her

parents to stay at their home. Late that night they passed in the hallway.

"He pulled me up against him, rubbed his hands up my body and under my cloths

and pulled me up against him. He rubbed up against me; I presume he had an

orgasm. He called me mammele.

Rabbi Milgram says she didn't tell her parents at the

time and wasn't able to work through the incident until three years later,

when she was 17 and on her first trip to Israel. Approaching the Kotel, she

saw Rabbi Carlebach leading singing there and she fled. Her companion saw

her distress and suggested that she "'pretend I'm him,'" recalls Rabbi Milgram.

"All I remember is screaming 'Who are you? Why did you do that? I was so

excited that you came to my house and then...'" (Today, Rabbi Milgram says,

she has come to terms with this event and feels very connected to Rabbi

Carlebach's positive work, though she had been alienated by her early experience

with him.)

For the past 15 years, Marcia Cohn Spiegel of Los Angeles,

has studied addiction and sexual abuse in the Jewish community and has spoken

to some 60 groups through Brandeis University, the University of Judaism,

the Havurah Institute, along with many Jewish women's organizations, synagogues

and Jewish community centers. She doesn't mention Rabbi Carlebach at all

in her talks, she told Lilith. Following such talks, women come up to her,

even in the women's bathroom, to pour out their own stories, she says, "not

seeking publicity or revenge, but coming from a place of shame and isolation."

Consistently through the years women have come forward to share their stories

explicitly about Rabbi Carlebach, Speigel says.

In a letter, which Spiegel made available to Lilith,

she states that in the last few years, a number of women in their 40s have

approached her "in private and often with deep-seated pain" about experiences

they had when they were in their teens. "Shlomo came to their camp, their

center, their synagogue," she wrote, "He singled them out with some

excuse...[G]etting them alone, he fondled their breasts and vagina, sometimes

thrusting himself against them muttering something, which they now believe

was Yiddish."

The other typical story, she says, is recounted by

women who had gone to Rabbi Carlebach, "for help with problems, or who met

him when they studied with him. They were in their 20s or 30s when it happened.

He would call them late at night (two or three o'clock in the morning) and

tell them that he couldn't sleep. He had been thinking of them. He asked,

Where were they? What were they wearing?"

A woman who attended services conducted by Rabbi Carlebach

in California in the 1970's, and who asked not to be identified in this article,

recalls precisely this second scenario. After meeting her once or twice,

she says, Rabbi Carlebach called her in the middle of the night several times.

"It was very creepy. I seem to remember him breathing heavily on the phone

and panting." Though at first she was confused, once she realized that "something

surreptitious" was going on, she told him not to call her in the middle of

the night anymore. He did not.

Rabbi Carlebach's sexual advances to adult women were

apparently well known. Rabbi Gottlieb herself recounts Rabbi Carlebach's

request that she pick him up at his hotel when he was visiting her Albuquerque

community. When she got there, "he refused to come down," asking instead

that she come up to his room. Rabbi Gottlieb "went up and stood outside the

threshold and said, "I am not coming into your room and you are not going

to touch me.'" Another woman recalls, "His manner was 'God loves you, I love

you,' and then he'd come on to you out of 'love.'"

If these allegations were so widely known, why were

so many people, in so many communities in the United States, Canada, Israel

and elsewhere, able to ignore or squelch such serious concerns to preserve

the myth of a wholly holy man?

The ideal time to confront Rabbi Carlebach about these

allegations would have been during his life. Though that opportunity has

passed, there are a number of reasons why these allegations need to be

acknowledged in public, even after his death.

First, silence. A silence protective of the man and

damaging to the women has been maintained for years, sometimes decades since

the alleged events. Perhaps these women were cowed by Rabbi Carlebach's living

presence, but his posthumous increase in stature cannot have made the speaking

easier. Those who have encouraged the women to come forward say they hope

that breaking these silences will help other women to speak as well, and

that such speaking will allow them all to begin to heal.

Second, power. It is important to understand just how

powerful and intimate an impact any spiritual leader, but particularly a

charismatic and revered Rabbi like Rabbi Carlebach, may have on followers.

Unfortunately, according to experts on clergy abuse, it is not uncommon for

extremely charismatic leaders to take advantage of this power in order to

make sexual contact with congregants. It is the rabbi's responsibility, these

women's stories suggest, to recognize his power, and to use it only to his

congregant's benefit and not to their detriment.

Finally, communal responsibility. In cases where a

rabbi's self-restraint fails, perhaps the Jewish community needs to look

at its own responsibility for protecting its members, and for helping its

rabbis as well. If Rabbi Carlebach's sexual advances indeed spanned decades

and continents, as has been alleged, and were indeed as well known as it

now appears, then we must ask: What might have been done on behalf of the

women who may have been hurt by him? What can be done for them today? And

why did the legions who revered him not do more to help him, since there

appears to be some evidence that Rabbi Carlebach was himself troubled by

aspects of his own behavior.

|

| Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach singing |

By the 1960's, Rabbi Carlebach was maintaining the

musical style and spiritual fervency of Hasidism, but had rejected constraints

and the gender segregation it demands. Among the ultra-Orthodox, wrote Robert

Cohen in a recent, generally positive memoir in Moment, "embracing women

was enough to make Shlomo a dubious, if not disreputable, figure in many

Orthodox circles." Instead, he established his base of spiritual operations

from the mid 60's to mid 70's at San Francisco's House of Love and Prayer,

a commune-style synagogue that catered to a young hippie community.

"Shlomo joined the counter-culture," notes Reuven Goldfarb

of a Berkeley Jewish Renewal congregation the Aquarian Minyan, defending

"Shlomo" (as the rabbi asked people to call him) from opprobrium. "The norms

in that sub-group were very different, and he was subject to all sorts of

temptation."

In addition to an increasing sexual openness in American

culture generally, Rabbi Carlebach had developed his own belief that the

healing of the world would come through unconditional love. He was known

for calling friends "holy brother," "holy sister," "holy cousin." "His life

goal," Cohen writing in Moment, recalled his saying, "was to 'hug every Jew

[sometimes it was every human being] in the world.'" One woman telephoning

Lilith from Jerusalem in horror that any negative story about Rabbi Carlebach

might appear, recalled, "he hugged many many people and he also saved so

many people with those hugs." Another told us, "He hugged into each man,

woman, child what each of us needed." Another man remembers a synagogue concert

in the late 60's when Rabbi Carlebach kissed every person who greeted him

there on the mouth.

Despite their support of some of Rabbi Carlebach's

spirituality and egalitarianism, there were even those in the forefront of

challenging Judaism's traditional hierarchies who viewed Rabbi Carlebach's

alleged sexual behavior as wrong. In the early 80's, a group of women in

the Berkeley area decided to express to him their concerns about his behavior

toward women. Among them was Sara Shendelman, a cantor who holds a joint

ordination from Rabbis Carlebach and Schachter-Shalomi and who sang with

Rabbi Carlebach for 15 years before his death. Specifically, says Shendelman,

her Rosh Hodesh group of 15 to 20 women was concerned that Shlomo Carlebach

did not observe proper boundaries with woman that he called them in the middle

of the night, and sometime invited them to his hotel.

"We were going to study Judith, supposedly, but what

we were really going to do was confront him," she recalls of the planned

meeting. The day came, and members of the group began to get cold feet. They

felt he just had "too much light" to be confronted, Shendelman recalls.

(Shendelman told Lilith she heard later that someone had told Rabbi Carlebach

the purpose of the meeting in advance. He came nonetheless.) The group, along

with Rabbi Carlebach, began to study. Rabbi Carlebach, according to Shendelman,

sat wrapped in his tallit and spoke of teshuva.

Not one of the women spoke up, until Shendelman announced,

"Shlomo, we came here because we need to talk to you about how you've been

behaving toward the women in the community And the whole room

froze. Nobody was willing to back me up."

The dialogue between Shendelman and Rabbi Carlebach

continued in a private room, where Rabbi Carlebach at first denied any problem,

says Shendelman. Then she reports, he said over and over, "Oy, this needs

such a fixing."

We cannot know what Rabbi Carlebach did toward "such

a fixing." Certainly the reluctance of the women of the Berkeley community

to approach him en masse, and the reluctance of others in the wider Jewish

community, must have made it easier for him to avoid addressing the problem.

Perhaps if he had received greater guidance in seeing that his behavior needed

repair, Rabbi Carlebach might have welcomed an opportunity to do teshuva,

repentance.

We do know that certain segments of the progressive

Jewish world, until the day Rabbi Carlebach died, distanced themselves from

him because they were aware of reports of his sexual behavior. Leaders at

ALEPH, and its sister organization, a retreat center called Elat Chayyim,

told Lilith that during Rabbi Carlebach's life they refused to invite him

to teach under their auspices or sit on their boards.

"It was definitely and issue for me," said Rabbi Jeffrey

Roth, director of Elat Chayyim, who says that he had hoped to invite Rabbi

Carlebach to teach before his sudden death. "My intent was&that I was

going to have a serious discussion about [the] innuendoes&In retrospect,

when I heard of the [seriousness] of the stories, I think that even my thinking

that maybe I would invite him and lay down the law would have been a cop

out."

"He didn't have a relationship with ALEPH, and that

[his sexual advances towards women] was a serious impediment," Susan Saxe,

chief operating officer of ALEPH, told Lilith, emphasizing that Rabbi Carlebach

was "one of several distinguished teachers with whom we might have wished

to be closer, but could not, in keeping with our Code of Ethics." ALEPH's

Code of Ethics proscribes the abuse of power in interpersonal relationships

as well as discrimination in other forms.

Rabbi Daniel Siegel, executive director of ALEPH, was

the first rabbi ordained by Zalman Schachter-Shalomi. He was introduced to

Rabbi Carlebach by his wife, Hanna Tiferet Siegel, to whom Rabbi Carlebach

"had been very kind during a difficult year in her life," Rabbi Siegel recalls.

"She always loved him for his support and encouragement."

"Shlomo was never my rebbe," Rabbi Siegel says, "though

I have a love both for his music and many of his teachings. In spite of the

disagreements I had with his politics and his very ethnocentric view of reality,

I brought or helped bring him for concerts several times. I was also aware

of his reputation for indiscretions with women, though what I heard was vague

and filtered through other people. However, it did happen that women I knew

began to tell me of conversations they had with him, after concerts I organized,

in which he said things which had disturbed or confused them. As a result,

I stopped inviting Shlomo, though I never told him why."

Now, however, the dam of silence has begun to break.

Some members of the Jewish Renewal community of Berkeley, California,

particularly those active in the Aquarian Minyan and the Jewish learning

center Chochmat HaLev, where Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb first presented her account

of Rachel's abuse last Fall, have taken upon themselves the burden of giving

voice to the allegations.

"He so deeply wounded many women," says Nan Fink,

co-director of Chochmat HaLev and co-founder of Tikkun magazine. "Communities

knew that this was happening, and women were hardly ever protected...I think

it is really important for the community to make a gesture of apology to

the women."

Rabbi Gottlieb's presentation came just eight weeks

before a scheduled Shabbat program entitled, "Celebrating Shlomo." According

to Reuven Goldfarb, a leader of the Aquarian Minyan, Rabbi Gottlieb's words

so disturbed some members of his community that the event was postponed until

after the community could begin a "healing process" and hold a series of

events to that end.

A Healing Committee has now been formed by the Aquarian

Minyan. On December 7, according to Goldfarb, a confidential meeting dubbed

Mishkan Tikkun; "a sanctuary for fixing" took place "to provide a listening

space for those who felt they had been injured by boundary violations that

occurred within a spiritual context." According to a source who attended

that meeting, three people came forward with claims against Rabbi Carlebach:

one woman spoke about herself, two spoke about their daughters.

Committee member Patricia Cohn, an interim director

of the now-closed Bay Area Sexual Harassment Clinic, told Lilith that the

Jewish Renewal community is attempting to address the concerns raised by

the allegations that have surfaced "by promoting opportunities for members

to talk with one another, gain support for dealing with their feelings and

reactions, re-establish, or establish, a deeper sense of safety, define

appropriate boundary-setting, and educate themselves about the way sexual

harassment functions and affects people." In addition, the committee hopes

to offer forums to "explore ethical and moral guidelines for rabbis and people

in positions of lay spiritual leadership to bring into focus the power imbalances

between someone in a position of spiritual leadership and the person he or

she is serving."

The Jewish world has not really dealt with rabbinic

[sexual] abuse," says Fink. "The Christian world has, the Buddhist world

has. The Jewish community needs to say, 'We don't sanction this.' The main

thing is to have it really be known that every infraction of this kind will

not be tolerated."

Nonetheless, for the many who knew Rabbi Carlebach

as a holy guide, hearing allegations may raise a conundrum: "How it is possible

that a person who can affect us so powerfully&can at the same time be

imperfect and do things we find very, very hard to countenance," asks Rodger

Kamenetz, author of The Jew in the Lotus and, most recently, of Stalking

Elijah: Adventures with Today's Mystical Masters.

This cognitive dissonance echoes through Jewish tradition,

which is filled with flawed leaders, Moses and David come to mind, who are

appreciated for their greatness and forgiven for their human failings. "It

is important for us to be reminded that even our spiritual teachers are flawed

human beings," notes Rabbi Siegel of ALEPH. "I hope that somehow, as time

goes on, we will learn how to honor Reb Shlomo's gifts and, at the same time,

to acknowledge those for whom his presence was difficult and even painful.

While I cannot predict how this will happen, I know that honest and open

discussion of the totality of Reb Shlomo's life can only help."

Indeed, the holding of both parts of Shlomo Carlebach

in mind have come into relief as these allegations against him have collided

full force with the reverence many still feel for him. Some of his followers

have jumped to his defense in the face of claims such as these. Lilith has

received both the outrage and prayers of those trying to stop the publication

of this article. Coming from as far as Israel, England, and Switzerland,

comments have ranged from denial that such actions could have taken place

to testimonials to his greatness. More than anything, these calls, emails,

and faxes have demanded in various ways that we perpetuate the silence.

"Whatever negative there is to say there [are] a million

positives you could choose," one protester wrote. Another told us, "He alone

gave me the sense of beauty of being a Jewish woman." A third, even more

adamant, suggested hat "there is no way you can even think of publishing

a negative article about a man like Rabbi Carlebach, if you even begin to

know the unending acts of kindness he devoted his life to performing." Finally,

some protested against these allegations coming to light, "regardless of

truth or right," "How dare you sully the memory of such a soul, such a tzaddik?"

one correspondent asked.

Kamenetz suggests that this need to see only the positive

sides of Rabbi Carlebach should be expected. "We want to be moved, we want

to be touched, and we project that onto certain individuals," he said, explaining

how such an idealized perspective develops.

Explains Rabbi Julie Spitzer, "It is not uncommon when

women come forward with their stories of inappropriate sexual contact with

a rabbi or clergy member hat the members of the congregation or community

so much want to disbelieve those shocking allegations that they vilify the

complainant and glorify the abuser." Rabbi Spitzer is director of the Greater

New York Council of Reform Synagogues and for 14 years has served on the

National Advisory Board for the Center for the Prevention of Sexual and Domestic

Violence.

In the cacophony of voices expressing doubt, fear,

fury and grief, Rabbi Gottlieb asserts, "This is about our relationship to

power, rabbinics, patriarchy. This is not about him. It is about the women

he hurt."

The voice of Rachel, speaking of her summer camp experience

more than 35 years ago rings clear for any who wonders why, in the end, her

story had to be spoken aloud. "I think in the name of a higher good than

one man's reputation, we must talk about this. It's about truth, and

if we keep saying that he was a great man and if we don't name the behavior

and don't hold him and his spirit and memory accountable, we are colluding

in perpetuating that behavior and violence in our most spiritual

center."

Sex, the Spirit, Leadership

and the Dangers of Abuse

By Rabbi Arthur Waskow - editor of New Menorah

Shalom Center

Two events in Jewish life raise serious questions about

the relationships among sexuality, spirituality, and religious leadership

-- questions of what it means to sharply separate sex from the Spirit,

and of what it means to confuse them without any boundaries.

One of these events is a letter that went in October

1997 from the dean of the rabbinical school of the Jewish Theological Seminary

to its students, and the other is the uncovering and publication by Lilith

magazine of some deeply disturbing reports describing abusive behavior of

Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, alav hashalom, z'l, toward some women.

The danger that religious and spiritual leadership

may slop over into sexual harassment and abuse seems to cut across all the

boundaries of different religions and different forms of religious expression

within each tradition. In Jewish life, for example, whether we look

at the most halakhically bound or the most free-spirit leadership, we find

some who draw on the deep energies of Spirit and the honor due teachers of

Torah, but cannot distinguish those energies and honor from an invitation

to become sexual harassers and abusers.

There are great dangers in totally sundering spirituality

and spiritual leadership from sexual energy, and there are great dangers

in treating the two as if they were simply and totally identical. The sacred

dance is to treat the two as intimately related but not identical.

For many of us -- not only in our own era and society,

but for example among the Rabbis of the Talmud too -- the energies

of Spirit and of sexuality are in truth intertwined, and need to flow together

for either to be rich and full.

Look at the Song of Songs, which is clearly erotic

and has been seen by many generations, using many different frameworks,

as deeply spiritual. Look at the Rabbis who said that Torah study was like

delicious love-making with a Partner whose sexual attractiveness never

lessened.

I would not want to lose this intertwining. Indeed,

I think that even in the aspects I have just named, some vitality was drained

from Judaism when the rabbis utterly separated the Song of Songs from its

erotic roots — forbidding it to be sung in wine-halls at the same moment

they approved its canonization as a voicing of the Holy Spirit and a book

of the Bible. And I think the Rabbis also drained some life-juice from Judaism,

as they themselves ruefully acknowledged, when they treated Torah-study as

so erotically fulfilling that they would forget to go home to make

love to their wives.

Just recently, the Dean of the Rabbinical School

of the Jewish Theological Seminary has warned its unmarried rabbinical students:

"Living together, which is the derech eretz of so many today, is unacceptable

for one seeking the rabbinate. . . . I want to make it clear that it is my

opinion that a rabbinical student 'living together' before marriage, even

with a future spouse, should not continue in the Rabbinical School." This

may or may not be a direct threat to dismiss any unmarried student who does

live with someone -- i.e., is publicly known to be in a sexual relationship.

Either way, I think it leads to deep spiritual and ethical problems.

|

| Shlomo Carlebach |

It was one thing to assume that sexual relationships

came only with marriage when people married in their teens. It is another

when our lives are so complex and our identities so fluid that many people

who are in rabbinical school are wise not yet to marry -- but also ought

not be forced to be celibate. The notion of forcing such students

into either long and complex lies about their sexual lives or into an undesired

celibacy means training future rabbis to be either liars or sexually warped,

narrowed, dwellers in Mitzraiim -- the "Narrow Straits."

Some might argue that the Dean's letter is not aimed

at the sexual ethics of Jews in general but at rabbinical students alone.

This is not factually correct; the letter makes clear that the Dean is concerned

about rabbinical students precisely because their behavior will affect the

behavior of all Jews, and it is the behavior of all Jews he hopes to shape

so that all sexual relationships are kept within marriage. For me the focus

on those who will become role models does not ease the problem, but may make

it worse. Who wants "role models" who have learned to choose between lying

and drying up?

Indeed, some believe that one way of creating sexually

uncontrollable people is to dam up their sexual energies when they are young

and should be learning how to channel them in decent, loving ways. Do the

demands of celibacy in some Christian denominations have any share in shaping

priests who abuse children or parishioners? Do Hassidic yeshivas that

forbid the bochers to masturbate, on pain of long fasts and punishment have

any responsibility when some of them never learn how to make loving love,

and become abusers when they grow older?

Taking all these issues into account, we need to explore

down-to-earth, practical steps toward shaping and celebrating sacred sexual

relationships other than marriage.

***********************

Is there any way to affirm and celebrate non-marital

sexual relationships, and to establish ethical and liturgical standards

for them, without violating halakha -- and indeed by drawing on some positive

strands of Jewish tradition?

From biblical tradition on, there has been a category

for legitimate non-marital sexual relationships that could be initiated and

ended by either party without elaborate legalities. It was frowned on by

most but not all guardians of rabbinic tradition. It was called "pilegesh,"

usually translated "concubine," though it meant something more open, free,

and egalitarian than "concubine" connotes in English.

I refer people to the recently published volume

by Rabbi Gershon Winkler, Sacred Secrets: The Sanctity of Sex in Jewish Law

and Lore (Jason Aronson, Northvale NJ). In it is an Appendix (pp. 101-142)

with the complete text of an 18th-century Tshuvah (Responsum) of Rabbi Yaakov

(Jacob) of Emden to a shylah (question) concerning the pilegesh relationship.

In it Rabbi Yaakov writes:

"[A single woman living with a man] ought to feel no

more ashamed of immersing herself in a communal mikveh at the proper times

than her married sisters.

"Those who prefer the pilagshut relationship may certainly

do so. . . . For perhaps the woman wishes to be able to leave immediately

without any divorce proceedings in the event she is mistreated, or perhaps

either party is unprepared for the burdensome responsibilities of marital

obligations. . ."

Winkler shows that Ramban (Moshe ben Nachman, Nachmanides)

in the 13th century and a host of other authorities also ruled that legitimate

sexual relationships are not limited to marriage.

It is true that some authorities, including Rambam

(Maimonides) did rule in favor of such limits, but many did not.

What are the uses of the pilegesh relationship? It

can give equality and self-determination to those women and men who use it.

Either person can end the relationship simply by leaving. It is true that

it does not automatically include the "protections" for women that apply

in Jewish marriages, but please note that the very notion of such "protections"

assumes that women are not only economically and politically but also legally

and spiritually disempowered, and need special protections. These

protections are an act of grace from the real ruler of a marriage -- the

husband -- to a subordinate woman.

But in our society, women are legally equal,

and often and increasingly economically and politically equal -- and

most of us want it that way. And our society is so complex that most people

defer marriage for many years, even decades, after puberty --

and most of us want it that way. So the value of the protective noblesse

oblige that the old path offered women must be weighed against the limits

on women's and men's freedom and emotional health and growth that are involved

in prohibiting sexual relationships between unmarried people, on the one

hand, and the limits on women's freedom and growth involved in traditional

Jewish marriage (e.g. the agunah problem) on the other hand.

To put it sharply --- do we really wish to forbid all

sexual relationships between unmarried people -- to insist on celibacy for

an enormous proportion of Jews in their 20s and 30s, and for divorced Jews?

If not, why not draw on the pilegesh relationship to establish a sacred grounding

for sexual relationships that are not marriages, and create patterns of honesty,

health, contraception, intimacy, and holiness for such relationships?

For us to draw on the pilegesh tradition in this way

does not require us to take it exactly as those before us saw it, or as others

might apply it today. For example, some Orthodox rabbis seem to be

using it today to help men who have become separated from their

wives but are refusing to give their wives a gettt, or Jewish divorce. If

there is no gett, neither spouse can marry again. But the pilegesh

practice lets the men find sexual partners and so reduce the pressure on

themselves to finish the divorce process. The "women in chains" who result

from this process cannot make a pilegesh relationship -- for under Jewish

law they would become adulterers, although their estranged husbands do not.

So in these cases pilegesh is used to disadvantage women even more.

But in communities that either do not require a gett

or recognize that either spouse can initiate a gett, and that would also

see pilegesh as a relationship that either women or men could initiate and

either could end, pilegesh could increase the free choices available

to women and become a way of celebrating sexual relationships that the parties

are not willing to describe as permanent -- especially relationships not

aimed at birthing or rearing children.

And the initial pilegesh agreement could specify what

to do in cases where a woman partner became pregnant, and how to establish

as much equal responsibility as possible between the pregnant and

non-pregnant partner.

If we both celebrate sexuality and do not believe that

"anything goes" in sexual relationships, then we are obligated to create

ethical, spiritual, and celebratory patterns for what does and doesn't go

in several different forms of sexual relationship. That is because

most joyfulness is enhanced by communal celebration, and most ethical behavior

requires not only individual intention but also communal commitment, embodied

and crystallized in moments of intense communal ceremony. This would mean

that we begin filling the pilegesh category with some ethical, ceremonial,

and spiritual content -- all quite different from the traditional patterns

for marriage, but also able to convey ethical and spiritual dimensions of

a different kind of sexual relationship.

And if the word "pilegesh," or its conventional translation

into "concubine," threatens to poison the idea, then let us honor the seichel

of those of our forebears who held this pathway open, and let us simply name

it something else. (For example, Israelis call the partners in an unmarried

couple a "ben zug" or "bat zug.")

In my book Down-to-Earth Judaism: Food, Money, Sex,

and the Rest of Life I draw on these alternative strands of traditional Rabbinic

law about which Rabbi Winkler has reminded us, to develop some new approaches

to a sacred Jewish sexual ethic for our generation. I had access to

Rabbi Winkler's research before his new book appeared, and want to urge people

to read it. I think he has done deep and great service to the possibility

of a Judaism that can speak to our generations.

***********

We have been addressing the danger of severing sexuality

from spirituality, and the possibility of celebrating this sacred intertwining

when it is best manifested in relationships other than marriage. On

the other hand, we must also address the dangers of treating spiritual

and sexual energy as if they were simply and exactly the same, so that spiritual

leadership might be taken as a warrant for sexual acting-out -- and in that

light we may explore ways of celebrating this sacred intertwining while

minimizing the chances of abuse.

The danger -- and the need for correctives -- became most poignantly clear to many of us when Lilith magazine published an investigative account of a series of molestations of adolescent girls by Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach. Reb Shlomo has been for many Jews of a wide variety of backgrounds an extraordinary treasure. His songs, his stories, his generosity in money and spirit have opened up not only Judaism but a sense of spiritual growth to tens or hundreds of thousands of people.

For me, Reb Shlomo was an important door-opener into

my own Jewish life. When I was profoundly discouraged by bitter attacks from

some Jewish institutions on The Freedom Seder and others of my early

efforts toward an ethically and politically renewed and revivified Judaism,

Reb Shlomo welcomed me as a chaver on his own journey into the wilderness.

He leaped and danced and sang at a Freedom Seder "against the Pharaohs

of Wall Street." He came to sing at a Tu B'Shvat celebration of "Trees for

Vietnam." He invited me to say one of the sheva brochas at his wedding when

I still knew too little Hebrew to do that celebratory task. He sat with me

for a television interview of "Hassidim Old and New" when the Lubavitcher

Hassidim (his old comrades) refused to be televised sitting at the same table

with either one of us -- him a "renegade," me a "revolutionary."

In a major break from the Hassidic past, he treated the women and men who

came to learn from him as spiritual equals -- even ultimately ordaining as

rabbis a few women, as well as men.

His love for Jews knew no bounds. So much so

that he could not believe that Jews could be oppressing Palestinians,

let alone criticize the oppression. As my own sense of an ethical and spiritual

Judaism came to include the need for a profoundly different relationship

between the two families of Abraham, and as his views crystallized into strong

support for the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, it became much harder

for me to work with him.

And as my own sense of self-confidence grew in pursuing

my own path toward the "new paradigm" of Judaism alongside the work of

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi and of a growing community of Jewish feminists,

my need for Reb Shlomo's reassurances vanished. My admiration of his

loving neshama remained, but I more and more felt that he was no longer pursuing

the deepest implications of Jewish renewal; that he was still too committed

to the old Hassidism to go forward in creating a new one.

And then I, and my friends, began to hear rumors,

a story here and there, more and more of them, about unsettling behavior

toward some of the women whom he was teaching. An unexpected touch

here, an inappropriate late-night phone call there. No stories that I would

quite call "horrifying," but stories troubling enough to make ALEPH: Alliance

for Jewish Renewal decide not to invite Reb Shlomo to teach at our gatherings,

When we heard that he and his staff were upset at this absence, we decided

to offer to meet with him face-to-face to say what was troubling us, and

hear his response.

But before we could go forward with such a meeting,

he died.

And then, after several years of grieving memory and

even, among some people, growing adulation, stories surfaced that were indeed

horrifying. Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb, herself a "rebbe" as well as a feminist

and a creator of Jewish renewal, brought some of the stories from secret

separate undergrounds into a public view: stories of physical molestation

of young adolescent girls, though not of what would be legally defined as

rape. An investigative reporter for Lilith found corroboration. Although

some people refused to believe the stories, and although it is a serious

problem that Reb Shlomo cannot himself respond to them, nevertheless it seems

to me that Lilith did a responsible job of checking on them.

How to square these stories with the Shlomo whom I

had loved and admired? With the Shlomo whose love of Jews had known no bounds?

Oh. "Whose love of Jews had known no bounds." No

boundaries.

From this clue -- no bounds, no boundaries -- I began

to try to think through what went wrong with Shlomo alongside what was so

wonderful about him, and why some who had loved him refused to believe what

by now seemed well-attested stories, and -- above all, since Shlomo-in-the-flesh

could no longer change his behavior -- what all that meant we should be thinking

and doing in the future.

For the "unbounded/ unboundaried" metaphor echoed for

me some of the teachings of Kabbalah and Hassidism, especially the ways in

which Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi had transformed those thought-patterns

toward a new Judaism. The ways in which he had reconfigured the Sphirot,

long understood as emanations and manifestations of God, as a framework for

human psychology as well. Truly the tzelem elohim -- the Image of God --

implanted in the human psyche.

What was the echo that I heard? It was the teaching

of the sphirah Chesed -- usually understood as "loving-kindness," but

in Kabbalah also understood as overflowing, unbounded, unboundaried

energy.

For me, then the question was and is, how to draw on

this echo, this insight, this "click," to celebrate the sacred intertwining

of sexuality and Spirit -- neither sundering one from the other nor confounding

their truths into a boundaryless mess.

How can we encourage this artful dance? We might learn

to shape and encourage a balanced embodiment of the Sphirot as the basic

character pattern of a spiritual leader — since one character-pattern

or another can prevent, or ease, or disguise a leaning toward sexual exploitation

of spiritual strength.

Kabbalah warns that the different Sphirot can become

distorted and destructive. We are most used to manipulation and abuse that

can flow from an overbearing overdose of the sphirah of Gevurah, Power and

Strictness, Of course Gevurah can inspire and teach. It may communicate

clarity and focus to those whose feelings, minds, and spirits are scattered

and dispersed. Yet there is danger in a teacher overmastered by Gevurah run

amok: one who teaches through raging fear and anger.

And a teacher overmastered by Gevurah may turn students

into submissive servants of his sexual will (far more rarely, hers).

We are less likely to notice the dangers

of Gevurah's partner Chesed, precisely because we are warmed by

loving-kindness. But --A spiritual leader may pour unceasing love into the

world. May pour out unboundaried his money, his time, his attention, his

love. For many of the community around them, this feels wonderful.

It releases new hope, energy, freedom.

But it may also threaten and endanger. Even Chesed

can run amok. A Chesed-freak may come late everywhere because he has

promised to attend too many people. He may leave himself and

his family penniless because he gave their money to everyone else. He may

give to everyone the signals of a special love, and so make ordinary the

special love he owes to some beloveds. And he may use Chesed to overwhelm

the self-hood of those who love and follow him, and abuse them sexually.

Indeed, this misuse of Loving-kindness may lead to

even deeper scars than naked Gevurah-dik coercion. For it leaves behind in

its victims not only confusion between Spirit and Sexuality, but confusion

between love and manipulation. That may make the regrowth of a healthy

sexuality, a healthy spirituality, and a healthy sense of self more difficult.

When we learn that a revered, creative, and beloved

teacher has let Chesed run away with him, and so has hurt and damaged other

people, what can we do? First of all, what do we do about the fruits

of Chesed that are indeed wonderful -- in Reb Shlomo's case, his music and

his stories? Some, particularly those directly hurt, may find it emotionally

impossible to keep drawing on them. I hope, however, that most of us

will keep growing and delighting in these gifts that did flow through Reb

Shlomo from a ecstatic dancing God. We do not reject the gifts that flowed

through an Abraham who was willing to kill or let die one wife and two sons;

we do not reject the gifts that flowed through an earlier Shlomo who was

a tyrannical king.

Certainly whoever among us have turned love and

admiration of Reb Shlomo into adulation and idolatry need to learn

to make their own boundaries, their own Gevurah. And we need to teach

the teachers who might fall into this danger of Chesed-run-amok, challenging

and guiding them, insisting and demanding that they achieve a healthier

balance.

To name one version of sexual abuse an outgrowth

of the perversion of Lovingkindness does not excuse the behavior. Like a

diagnosis, it distinguishes this particular disease from others that may

also become manifest as sexual abuse. Dealing with Chesed-run-amok is different

from dealing with Gevurah-run-amok.

Chesed needs to be balanced by Gevurah's Rigorous

Boundary-making, and the two must reach not just toward balance but toward

the synthesis of Tipheret or Rachamim, the sphirah of focused compassion

-- traditionally connected with the heart-space.

Why there? The heart is a tough enclosing muscle that

pours life-energy into the bloodstream. If the muscle were to go soft and

sloppy, or be perforated by holes, it could no longer squeeze the blood into

the arteries. If the blood were to harden and become Rigid, it could not

flow where it is needed. In the same way, Rechem -- the womb

-- is a tough enclosed space that pours a new life into the world.

Chesed alone, Gevurah alone, bear special dangers.

Even so, each of them remains part of the truth, the need, and the value

of God and human beings. Perhaps the character orientation most likely

to encourage a teacher's ability to pour out spiritual, intellectual, and

emotional warmth without turning that into sexual manipulation is a character

centered on Tipheret/ Rachamim.

**********************

Finally, we must deal with the danger that a

teacher's "shaping-power" may turn into domination. When either

Chesed or Gevurah gets channeled into the notion that a teacher owns this

power -- is not, one might say, one of God's "temporary tenants" of

this loving or awesome property but is its Owner -- then the submissiveness

this invites, creates, and enforces becomes idolatry. The teacher who

invites this idolatry is an idol-maker -- far more responsible for it than

the student who may thus be tricked into idol worship.

There are two ways to prevent this kind of idolatry,

this transmutation of spiritual energy into abusive behavior. One way is

to limit the power-holder's actions. The other way is to empower the one

who feels weak. Both are necessary.

One of the most powerful practices for both reminding

the powerful of their limits and empowering those who begin by thinking they

are powerless is one I have seen Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi carry out many

times.

On Erev Shabbat or Erev Yomtov, he might begin what

looks at first like a classic Chassidic "Tisch" or "table":

The Rebbe sits in a special chair, and for hour after

hour teaches Torah to the assembled multitude, who sing and sway and chant

with great intensity. Consumers, all of them, of his great wisdom.

So Reb Zalman would sit in a special chair at the head

of the dinner table, and teach Torah -- but only for 20 or 30 minutes. Then

he would stand, say "Everyone move one seat to the left" -- and he would

move. He would nod to the member of the chevra who now sat in the Rebbe's

Chair, saying: "Now you are the Rebbe. Look deep inside yourself for the

Rebbe-spark. When you have found it, teach us. And all us others -- we must

create a field of Rebbetude, an opening and beckoning to affirm that you

too can draw on Rebbehood."

It worked! Over and over, people would find the most

unexpected wisdom inside them, and would teach it.

The real point of this powerful but momentary practice

was to embody its teaching in all the other moments of our lives.

To be a "rebbe" is to live in the vertical as well as horizontal dimension

-- to draw not only on the strength of friends, community, but also on the

strength that is both deep within and high above. No one is a rebbe all the

time, and everyone should be a rebbe some of the time.

This is not at all the same as simply saying that all

of us are Rebbes, stamm -- even just part of the time. All of us are potential

"part-time" Rebbes -- if we choose to reflect on our highest, deepest selves.

And that means we are less likely to surrender our souls and bodies to someone

else. A true Rebbe, it seems to me, is one who encourages everyone to find

this inner spark and nurse it into flame. But we have all bumped into people

who act as if they are the flame, while others are but dead kindling-wood.

To say that any one of us is empty of the Spark is

to deny God's presence in the world. To arrogate the Spark to one's own self

alone is to make an idol of one's ego. Reb Zalman's practice

teaches another path -- and I believe that if we were to develop a number

of similar ways to walk it, there would be far less danger of spiritual/

sexual abuse.

|

| Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach |

And that we also counsel congregants, students, clients

to strengthen the aspect of their Self that is one flame of God; that they

not try to gain confidence by subjugating their own sense of self to someone

else; that they choose a sexual relationship out of strength, not weakness.

ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal chose five years

ago to make this clear through an ethical code that prohibits any teacher

or other spiritual leader from using that position during a class or a Kallah

or similar event to initiate a sexual relationship with a student or learner.

Even more important, ALEPH made sure that this ethical code was publicly

announced to and discussed by all teachers, leaders, and other participants

-- so the discussion taught a deeper lesson, one that could last beyond the

immediate situation into the longer future.

In this way we can embody the hope that two people

have in truth a deep connection with a holy root -- for if so, it will last

long enough to be pursued when the two stand much more nearly on a firm and

equal footing. And we can also embody the wisdom that true spiritual leaders

and true spiritual learners can approach each other not bound in a knot of

manipulation with obeisance, but with mutual respect.

Indeed, if we intend to require our teachers to refrain

from sexual abuse, then we must also encourage the balanced expression of

a sexuality that is ethically, spiritually rooted. We must seek new ways

of making sure that our teachers find others of the same depth and intensity

to become their partners.

This would be sexuality filled with Kavod: the kind